Space sector highlighted by Central Committee in recent Qiushi issue

The fourteenth issue of Qiushi for 2024 highlighted China's Space sector along with its numerous achievements.

China’s space sector was recently highlighted in the fourteenth issue of the 2024 run of the Qiushi (求是) magazine. The article in the fourteenth issue was written by Bao Weimin (包为民) and is titled China Aerospace: The exploration of the vast starry sky never stops (中国航天:星空浩瀚 探索不止), published online July 16th 2024. Bao Weimin's article discusses China's recent exploration successes, economic and development benefits, and future prospects for the sector. I find these areas fascinating, so let's look at the article.

Before we begin some context is required for those outside of the loop on the political landscape of China. Qiushi (求是), or ‘Seeking Truth’ when translated to English, is a theoretical and news journal of the Communist Party of China (CPC) published by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China twice a month. Articles written inside a Qiushi issue are written by senior officials of the CPC, like Xi Jinping as well as provincial and ministerial officials, along with contributions from China’s various academic institutions and think tanks. Bao Weimin (包为民) is currently Vice Chairman of the China Association for Science and Technology, Academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Director of the Science and Technology Committee of China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation.

Economic & Development Benefits

Much of the article is dedicated to how China has utilized space to expand and serve economic and social development at home and abroad. Bao Weimin argues that this is performed through navigation, communication, and remote sensing satellites.

Navigation Satellites

China notably operates its BeiDou series of navigation satellites to provide geolocation services to users worldwide. BeiDou has been continuously operated and upgraded since 2000 when the BeiDou-1 system came online and began providing services across China. BeiDou-2 later served the Asia-Pacific region with completion in 2012, and BeiDou-3 has been providing worldwide services since its completion in 2020.

According to the article, the three generations of the system have allowed for the inclusion of new hardware such as high-performance atomic clocks and inter-satellite links.

Consistent development and construction of the Beidou network has allowed it to be used by half of the world allowing it to become an internationally recognized advanced system, Bao Weimin argues. This is widely agreed on as the system has 1.5 billion users as of November 2022 across 230 countries and regions according to Ran Chengqi, who is the Director General of the China Satellite Navigation Office and Spokesperson of the BeiDou Navigation Satellite System.

Communication Satellites

Like any major aerospace player, China operates, manufactures, and sells communication satellites. Development of the country’s domestic communications began with the launch of DongFangHong-1, which was China’s first satellite in April 1970. China’s first domestic geostationary communications satellite, DongFangHong-2, launched in April 1984 and was the first of five to do so. These initial efforts were supported by Deng Xiaoping and Zhou Enlai, both major political leaders during China’s modernization and ‘economic miracle’.

The article argues that since the launch of these initial communications satellites China has switched from solely being for practical use to commercial use as well. Bao Weimin argues in support of this that the number of supported terminals in use has increased by a factor of ten thousand. While true it is worth mentioning that in the same time period the GDP, gross domestic product, of China increased from approximately 300 billion to 17.96 trillion United States Dollars, as such a large increase of communications terminals is not unheard of as the country modernized. The various DongFangHong satellite platforms are also mentioned as an example of “flourishing and growing” domestic capabilities. This is reinforced by the China Academy of Space Technology alone offers four different communications satellite platforms depending on customer needs and budget, some unlisted satellite platforms are believed to be reserved for military use due to them utilizing ‘cutting edge’ technology.

Remote Sensing Satellites

Remote sensing satellites are perhaps what those uninitiated to China’s space sector are most familiar with, outside of its human and science exploration efforts, due to how regularly they are launched. According to Bao Weimin, remote sensing satellites that are used for agriculture, forestry, ocean, land, environmental protection, and meteorology have an imaging resolution of 0.5 meters. Satellites with a resolution of 0.5 meters make their observations via synthetic aperture radar, laser, hyperspectral, visible light, and infrared methods.

The article also says shortly after that “public welfare civilian visible-light satellites” can image a large majority of China regularly with a 2-meter resolution. These satellites are placed between low orbits, like sun-synchronus orbit, and geosynchronous orbits. China’s fleet of over 200 remote sensing satellites have been key in efforts like food security. Bao Weimin ends the section on remote sensing satellites by saying:

“Through remote sensing satellites, we can not only feel the temperature of the world, but also see subtle changes in the world.”

Economic & Development Benefits Figures

Ending the section on the economic and social development benefits Bao Weimin shares some figures. The first is the number of BeiDou terminals on vehicles, which are as follows: approximately 8.3 million road vehicles, nearly 50,000 ships, 2,100 aircraft, along with 200,000 automatic driving agricultural machines.

The second set of figures, which I find more interesting, is the output value from satellites. For 2023, the stated overall output value of China’s satellite navigation and location services industry reached 536.2 billion Yuan, or 73.7 billion United States Dollars, and the output value from satellite navigation services and applications reached 375.1 billion Yuan, or 51.5 billion United States Dollars. The combined total of both of these figures is 911.3 billion Yuan, or 125.2 billion United States Dollars. These figures for output value have been known for a few months, but are impressive nonetheless.

Human & Robotic Exploration

Leadership and senior officials have been keen to promote China’s efforts to become a strong aerospace nation. As such, the article spends a good deal of its content discussing the country's robotic and human exploration.

Human Exploration

China’s most remarkable and complex achievement in its exploration endeavors is currently the completion of the permanently crewed three-module Tiangong Space Station, in low Earth orbit. The article mentions that the Central Committee signed off on China’s human spaceflight plans in the 1990s as part of a ‘three-step’ development strategy. Shenzhou-5, in October 2003, was the ‘first-step’, demonstrating the capability to send humans to and from orbit safely.

The ‘second-step’ was a series of technological developments such as rendezvous, docking, human extravehicular spacewalks, and on-orbit supply delivery. This was achieved by the first two Chinese space stations (which were operated between September 2011 and July 2019), the Shenzhou-7 mission in September 2008, and the Tianzhou-1 mission in April 2017.

China’s third and final ‘step’ was the construction of its three-module Tiangong Space Station in low Earth orbit between April 2021, for the launch of the core Tianhe module, and November 2022, when the Mengtian laboratory module was relocated to its current and permanent position. Bao Weimin reasons that with these ‘three-steps’ completed China can focus on utilizing the space station as a space laboratory and as a symbol of China’s scientific achievements. Supporting this claim in December of 2022, the same month the Shenzhou-15 mission began, the China Manned Space Agency began the application and development stage, which will last ten years to enable technological advancements as well as solving scientific challenges. Alongside this, the Tiangong Space Station has been permanently crewed since June of 2022.

Robotic Lunar Exploration

Uncrewed lunar exploration is arguably a field China leads in the 21st century. So far China has performed nine lunar missions, all successfully. Bao Weimin highlights four of the Chang’e missions in the article.

The four highlighted Chang’e missions are; Chang’e 1, China’s first lunar orbiter and mission launched in October 2007; Chang’e 4, the first lunar lander to touch down on the Moon’s far side, launched in December 2018; Chang’e 5, a lunar sample return mission launched in November 2020; and Chang’e 6, a lunar far side sample return mission launched in May 2024, and the first ever performed. After highlighting these missions, and particularly Chang’e 6, the article argues that China’s Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP) has “embarked on a path of high-quality, high-efficiency lunar exploration” along with further promoting win-win cooperation.

Nine successful lunar missions with no failures itself is arguably proof enough of “high-quality, high-efficiency exploration”. The European Space Agency has been a consistent collaborator with China’s lunar exploration by providing access to ground stations during major portions of missions in exchange for flying scientific payloads. Samples from lunar missions have also been shared with international organizations, which will soon include NASA.

Robotic Mars Exploration

Despite being a relative newcomer, China has already made great strides in deep space exploration. Tianwen-1 was the country’s first mission beyond the Earth-Moon system and saw a probe entire orbit of Mars, and later send a lander to the surface. This mission is particularly remarkable since it consists of three major parts that only the United States of America was able to deploy for years until May 2021. The key components were an orbiter, a lander, and a rover. Performing all of this in a single mission represented a significant advancement in China's deep space exploration capabilities.

Bao Weimin also highlighted the massive advancements Tianwen-1 displayed while adding that the rover, named Zhurong, receives its namesake from the God of Fire in Chinese culture. While shorter than the previous two, the section of the article dedicated to robotic Mars exploration claims that with the success of Tianwen-1, China has established itself as a leader in interplanetary exploration. While I believe China should complete additional missions successfully before making that claim, at least three more significant interplanetary exploration missions are scheduled for launch before 2030.

Future Plans

The final part of Bao Weimin’s article is dedicated to the future of China’s space sector. This includes future missions, future launch vehicles, and ways China could better utilize space to meet the country’s scientific, development, and economic goals.

Future Missions

Tianwen-2, Tianwen-3, and Tianwen-4 are highlighted first as ways to promote deep space technology advancements as well as for scientific and exploration prestige. Tianwen-2 is an asteroid sample return mission that is expected to begin in 2025; Tianwen-3 is a Mars sample return mission, and may be the first mission to return samples, which is expected to begin before 2030; Tianwen-4 is a mission to explore Jupiter and its moons with an expected launch in 2029. Successfully completing these missions would place China as an equal to the European Space Agency and United States in the field of deep space exploration.

Chang’e 7 and Chang’e 8 are also touched on as both missions are building off of technology and experience from the previous six missions to establish a robotic research ‘station’ on the lunar surface. Both missions are expected to land near the lunar south pole to search for potential resources and unique samples for collection on later missions. Chang'e 7 is expected to launch in 2026, with Chang'e 8 following in 2028. These missions will also play a key part in the initial stages of the China-led International Lunar Research Station.

China’s plans for a crewed lunar landing before 2030 is also touched on, mainly as a way to promote scientific and exploration projects. Human spaceflight is arguably the best way to promote spaceflight overall, especially as the requirements to become an astronaut come down as risk is lowered. No firm date has been given for a potential first landing yet, but I believe it will occur before China’s National Day in October of 2029.

It is quite possible that a crewed mission will be on the surface during that year's National Day. This would coincide with the 80th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China, the founding is also why the National Day takes place in October. A National Day lunar crew would likely be the second taikonauts to step foot on the surface to reduce schedule risk to the first landing mission. China is also no stranger to including space achievements in its celebrations.

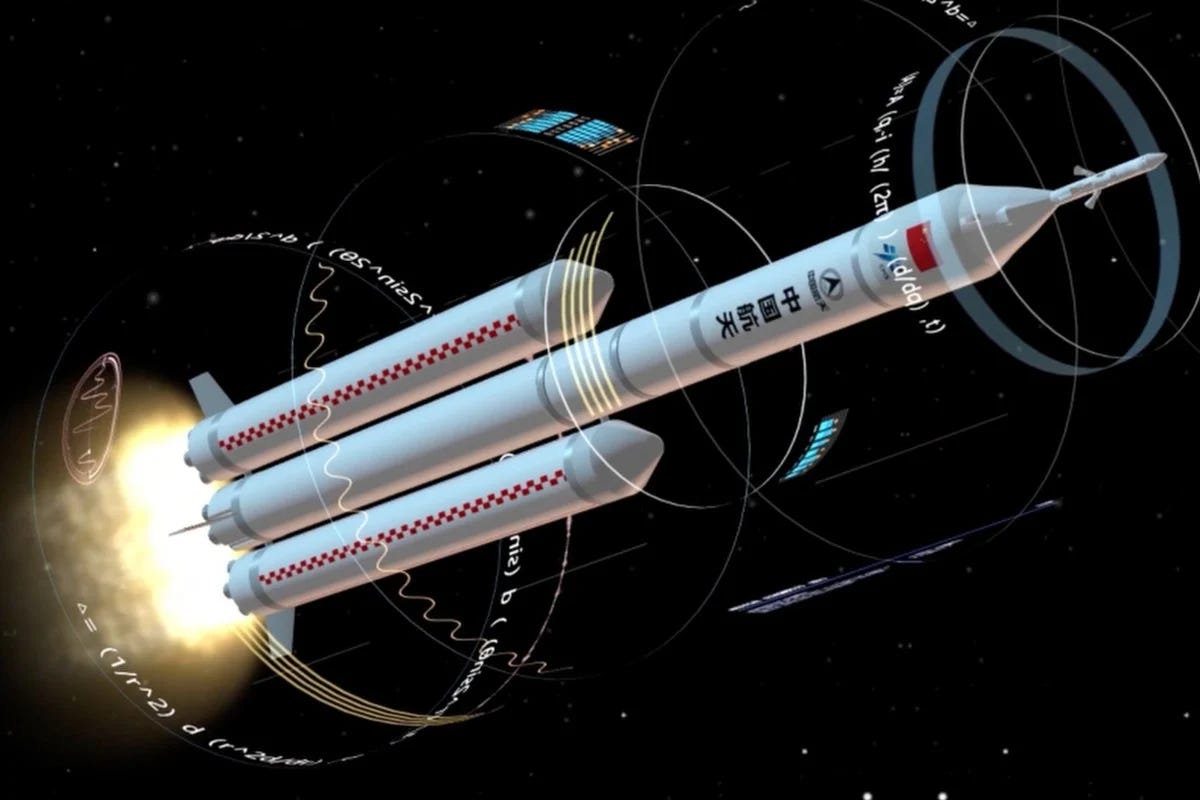

Future Launch Vehicles

The Long March 10 is the only future launch vehicle mentioned by name in the article, it is scheduled to debut around 2027. China's ambitions for a crewed lunar landing rely heavily on the Long March 10, which requires two launches for each landing. Currently, the payload capacity is anticipated to be 70 tons for low Earth orbit and 27 tons for a translunar mission. The Long March 10A, a smaller variant of the launch vehicle, is scheduled to debut before it, with a carrying capability of at least 14 tons to low Earth orbit.

While none were mentioned by name, emphasis was placed on developing new launch vehicles that are low-cost, high-performance, and reusable. Between China’s state-owned and private launch companies, over a dozen reusable launch vehicles are currently believed to be in development. Low-cost, high-performance, and reusable launch vehicles are believed to be key in solving two problems: creating a highly active commercial launch market and the use of hypergolic-fueled launch vehicles.

Launch priority on China’s more capable vehicles is believed to be allocated to state-related projects and satellites, with over half of 2023’s new satellites being related to a state project or institution. In terms of tonnage sent into space, state-related spacecraft dominate substantially.

Despite the emergence of cleaner-fueled launch vehicles in recent years, China is still reliant on older hypergolic-fueled vehicles. These vehicles, while affordable due to years of mass production, use toxic fuels that are harmful to be near without protective equipment. Newer clean-fueled rockets are flying, and increasing production impressively year-over-year, but not enough to win out, in terms of cost and reliability.

An active commercial space sector using non-hypergolic rockets would speed up China’s transition away from reliance on toxic propellants. Bao Weimin argues that having reusable low-cost launch vehicles would build a “space transportation system that benefits people's livelihoods”. Having more space infrastructure launched at a low cost would benefit China’s development and speed up poverty alleviation efforts, thus benefiting people’s livelihoods.

Future Space Infrastructure

Toward the end of Bao Weimin’s Qiushi article, focus is given to new ways China can use space, and what infrastructure should be placed on orbit. For efficient use of space, the article argues for the realization of “one satellite with multiple capabilities and multi-satellite networking”, this is likely referencing various plans for satellite constellation in Earth and lunar orbit.

Plans are already underway for the Queqiao Lunar Satellite Network to provide communications and location services to spacecraft and human users on and around the Moon. China also has plans to launch tens of thousands of satellites into low Earth orbit through a mix of state and private industry-backed plans. These constellations are planned to provide internet and communications services to users worldwide. Both of these constellations would effectively end SpaceX’s near-monopoly on high-speed satellite internet. When operational, the Queqiao Lunar Satellite Network will provide a feasible alternative to costly Earth-based communications infrastructure for nations and companies seeking to conduct lunar missions, the network would also provide more consistent communications.

Bao Weimin also suggests that an on-orbit “space shop” should be established to perform maintenance, upgrades, and construction on satellites already in space. Maintaining and upgrading satellites in space could reduce costs over extended missions while providing intermittent capability improvements. Constructing on orbit will allow for larger complex satellites that wouldn’t survive launch, or for spacecraft that would be too large to fit on launch vehicles. Few details were given on a “space shop” but it is likely something that China is pursuing due to its plans to incorporate space-based solar power stations in its net-zero ambitions.

Closing Thoughts

While this Qiushi article did not contain much new information regarding missions happening soon, I believe what was discussed is indicative of continued political support in the short and long term. Bao Weimin also indicated that China will continue to follow its aerospace dream using its technological breakthroughs to reach new heights.

This article also provided an extensive look back at the numerous advancements made in recent years.

Why pay attention to Qiushi?

As the theoretical and news journal of the Communist Party of China, Qiushi indicates possible future direction and policy of China in a wide range of areas. Space is one of the area’s Qiushi covers, either through articles written by members of the party or reprints of content from the Xinhua News Agency.