China Appears to Have Refueled a Geostationary Satellite in World-Leading Test

Shijian-25 and Shijian-21 are no longer docked following what may have been a successful satellite-to-satellite refueling test.

Throughout the year, China is believed to have been testing autonomous in-space refueling via the Shijian-25 (实践二十五号) refueling technology verification spacecraft, launched in January, and Shijian-21 (实践二十一号), primarily tasked with debris mitigation, in geostationary space.

During much of the year, the two involved satellites gradually headed towards each other. In late June, what appears to be a docking rehearsal took place with the two satellites, followed by a reapproach, and then docking in late July when they became indistinguishable from each other following a likely docking and beginning of the satellite-to-satellite refueling test. That was followed by a period of no externally observable activity, a joint burn to reduce orbital inclination in August, and then a few months of inactivity.

At the end of November, new activity was spotted between the two Shijian satellites with s2a systems capturing an image, via telescopes on Earth, of the two after separation a few days earlier. On December 3rd, COMSPOC, a space situational awareness firm, shared a data-driven animation and analysis of the two satellites’ separation, writing:

“On 25 November at 06:33 UTC, [Shijian-25] executed an in‑track burn that lasted about 40 minutes and imparted roughly 0.13 [meters per second1] of delta‑v2 — consistent with an undock or separation maneuver. Both [Shijian-21] and [Shijian-25] performed further adjustment maneuvers in the following days. They have remained in proximity, averaging under 10 [kilometers] over the past two days, but are clearly two distinct objects. Both have a mean longitude of about 127.2°E, positioned over China.”

As noted by COMSPOC, the two Shijian spacecraft have separated and both performed maneuvers to do so, indicating that their propulsion systems are operational after a likely refueling of Shijian-21. Although the small burns are not wholly indicative of a refueling, that will be confirmed via an energy-intensive burn from Shijian-21 to head elsewhere.

For now, it can be safely assumed that Shijian-25 provided some propellant to Shijian-21 following a pioneering geostationary satellite-to-satellite refueling test ahead of its use on various operational satellites.

Once again, I must stress that for proper details regarding the test, we will have to wait for official word from one of China’s space agencies or enterprises, which may announce the success of the test anywhere from a few days to several weeks afterward. Confirmation may come in the form of an extensive technical recap document or as a passing mention in a work report.

As for what’s next with Shijian-25 and the now topped-up Shijian-21, that’s unknown. Shijian-25 may refuel another satellite (maybe Shijian-23, Shiyan-12-01, Shiyan-12-02, or TJSW-3), while Shijian-21 could perform another debris mitigation demonstration after its first in late 2021. Alternatively, they could dock to each other again.

Back in August, Jim Shell, a space domain awareness and orbital debris expert, provided another theory (which I don’t entirely buy) that one of the satellites is preparing to inspect a U.S. satellite from the USSF-44 mission, launched in November 2022, after undocking as they are now on nearby orbital planes. From myself, a wildcard idea for what’s next may include the recently launched Shijian-28 (实践二十八号), as absolutely nothing is known about the potentially 7,000-kilogram spacecraft. As such, Shijian-28 could be for anything from communications, missile warning, intelligence, or a propellant depot around geostationary space for Shijian-25-like satellites to top up from.

What do we know about the satellites?

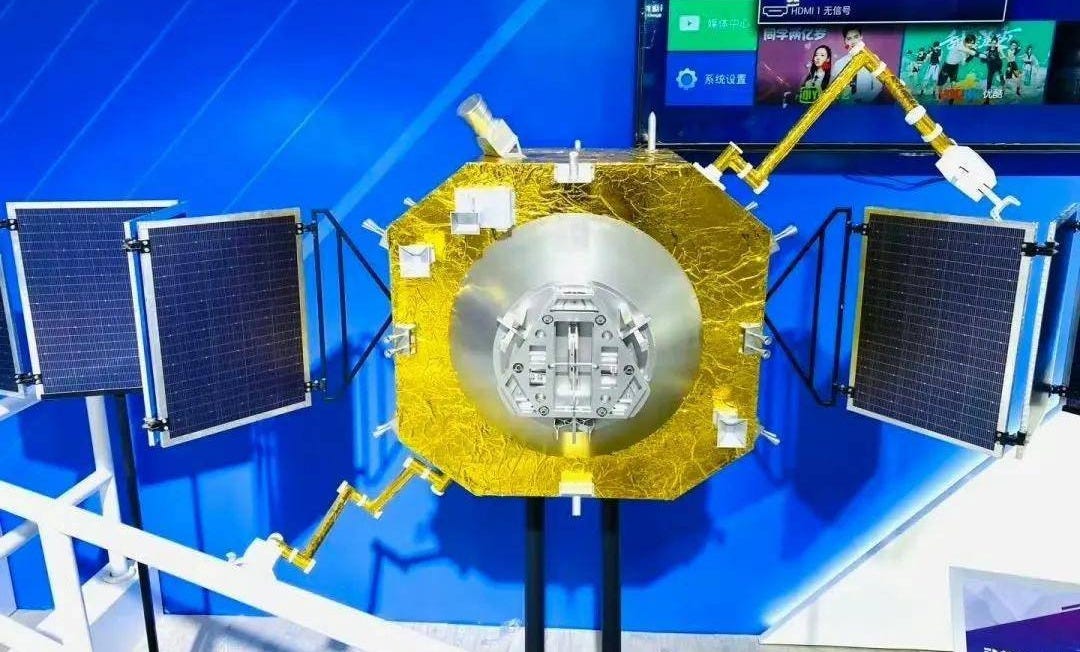

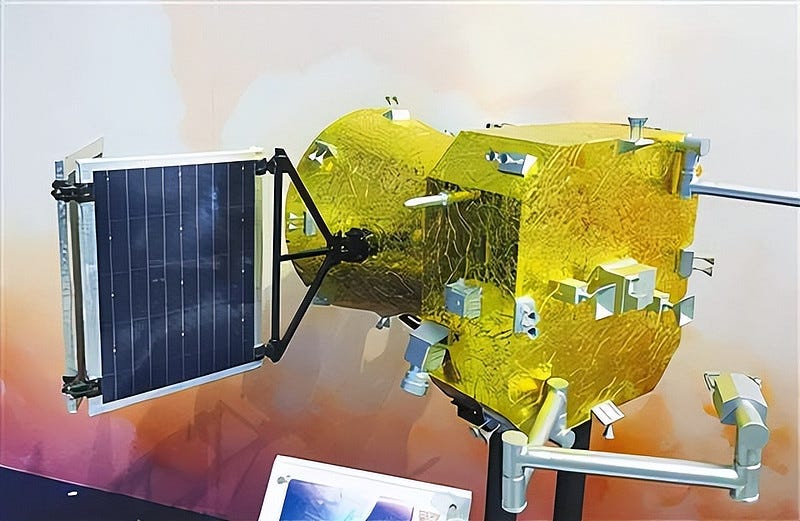

Limited information is known about the Shijian-25 and Shijian-21 spacecraft, other than that they were both made by the Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology (上海航天技术研究院). But at the 2021 China International Aviation & Aerospace Exhibition (中国国际航空航天博览会), commonly known as the Zhuhai Airshow (珠海航展), details shared at the Shanghai Academy’s booth of a servicing-refueling spacecraft state:

“The refueling spacecraft can carry 1.3 tons of fuel at one time, accounting for fifty-two percent of its own weight. It can be called a ‘space mobile tanker’. For a satellite that is ‘in urgent need of rescue’, it only needs to add 50 kilograms of fuel, and the satellite can extend its life by about one year. Compared with the cost of re-launching a geostationary orbit satellite, the cost is reduced by thirty-five percent. Therefore, the realization of on-orbit fuel refueling technology is tantamount to timely assistance for expensive satellites.”

“After receiving the help signal from the satellite with fuel shortage, the vehicle will be guided by the ground dispatch system to the rear of the satellite, and use the navigation system to track and approach the satellite autonomously. When it arrives within about two meters of the satellite, with the cooperation of the robotic arm, it will achieve a close connection with the satellite refueling port and deliver fuel to the satellite.”

If there are any problems with this translation please reach out and correct me.

World-leading technology?

As the refueling test between Shijian-25 and Shijian-21 has now likely been performed and concluded, China today leads in-space refueling and servicing technologies, having already demonstrated robotic satellite servicing. With that lead, China may begin refueling spacecraft currently utilizing its standard connector (it’s unknown how many satellites have that) and possibly begin providing it as an add-on service for countries that buy satellites from China. Additionally, the country may begin extending the operational lives of its communication, missile detection, and intelligence spacecraft.

While the test has been happening, U.S. Space Force officials have been complaining to news outlets about the advancements demonstrated, alongside a possible lack of superiority in space, despite having an eyewatering budget of forty billion United States Dollars and ending support for similar demonstration missions. Luckily for them, NASA has conveniently recently found that no technical barriers are limiting in-space refueling in geostationary space, and a private firm plans to provide a military satellite with a tiny amount of propellant.

Outside of the military, private capital is currently driving remaining American efforts (seeking emerging technology monopoly profits), with SpaceX leading the U.S. plans via a transfer of propellant using its Starship vehicle, but the vehicle has been stuck with limited development following regular failures3, holding up orbital flights needed for the next major step in development, like a Starship-to-Starship propellant transfer. Behind them, Northrop Grumman is at a similar stage of development to Shijian-21, with refueling in space set to come later.

Video originally from COMSPOC_OPS on Twitter, video from Tweets cloned to YouTube for archival.

Meters per second for in-space burns refers to how fast a spacecraft changes its velocity when firing its engines.

Delta-v is a measure of the impulse per unit of spacecraft mass needed to perform a maneuver in space.

From SpaceX Is Eyeing a Potential IPO, It May Cost Them Mars:

During 2025, the development program had regressed significantly in terms of progress. In June, Ship 36 unexpectedly exploded during a routine test, wiping out a critical pre-flight test stand with it. Meanwhile, during flight tests of the vehicle, Ship 33 was lost due to a fire in its engine section in January. Next in March, Ship 34 was again lost in a fire. Then in May, Ship 35 was destroyed during atmospheric reentry following leakages across the vehicle. 2025’s progress peaked at previously achieved milestones on par with an older design, while delaying expected NASA milestones.

That's an amazing feat by China and one that will be loudly heard . So guys , just imagine the precise locating of source and target sattelites , then manoeuvring them by raising or lowering orbit as both the sattelites have different orbital speed , then docking them with each other , refuelling , then un-docking , again manoeuvring and changing orbits . This capability that China achieved is significant and keep in mind that no other Country has done this refuelling feat in space yet.

Well Done China!

Fascinating to see China closing the gap in on-orbit servicing. The autonomous docking at GEO and fuel transfer is no small feat, especially considering the precision needed at that altitude. What's intresting is the cost comparision they mentioned - 35% less than relaunching makes this economically viable for extending sattelite life. I wonder how this will reshape the busines model for commercial sattelite operators once this tech gets more standardized.