China Is Not Racing to the Moon

Slow and steady wins in the long term.

This decade will see humans return to the Moon from two nations, the United States and China. China plans to land its first two taikonauts before 2030 (with hints of a 2028 landing), while the U.S. expects to land a crew of two astronauts in 2027 through the Artemis program. The landing of two American astronauts will be the first since 1972, whilst the two taikonauts will be the first Chinese spacefarers to step foot on the Moon.

In recent years, the United States has portrayed its return to the Moon as a race against China. Former NASA Administrator Bill Nelson (2021-2025) and Republican Senator Ted Cruz have “warned” that China could land astronauts there first, framing it as a challenge to American leadership in space. But China doesn’t share that view.

While the U.S. has tried to lean on the idea of competition to secure political and financial support, China treats its space and lunar programs as part of long-term plans for national development. This difference is part of a contrast in political systems and strategic goals.

China’s crewed lunar program is guided by centralized, long-term planning tied closely to national priorities. Backed administratively by the China National Space Administration, flown by the China Manned Space Agency, and produced by the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation as well as its subsidiaries, the program supports economic growth, advances key industries, and contributes to broader development goals. All of which China wants to modernize and innovate.

With few political shifts and more stable funding, China doesn’t need to frame its lunar program in a race with the U.S. plans. As a Marxist party-state, China’s major policy decisions come through the ruling Communist Party of China (CPC) alongside the National People's Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). The three political entities set long-term national objectives through central planning and consultation of academics who are specialists in their field.1

Policy proposals, including those related to space, are shaped through a network of think tanks, academic institutions, and knowledgeable academics2 (some within the CPC, NPC, or CPPCC). These bodies provide research and strategic analysis into China’s decision-making apparatus, particularly the State Council. Once a policy and its direction are decided, it tends to receive consistent support over many years, with progress evaluated against clear developmental and technological milestones. This structure means the space program is not vulnerable to the kind of budgetary uncertainty or political turnover common in Western liberal democracies.

Contrast this against the United States, where NASA operates within a shifting political landscape where priorities can change every four or eight years. Major programs like Artemis need to win support from both Congress and the White House, often across multiple administrations. This makes long-term planning difficult and forces NASA to secure its plans through broader political messaging.

Framing the Artemis program as in a race with China helps build urgency and supposedly protects funding (for now). It gives lawmakers a reason to back expensive programs, even when timelines slip or costs rise. But this urgency stems from structural limits. As Wu Weiren (吴伟仁), Chief Designer of the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program, noted:

“When the president changes, his policies change,” — “We in China may anchor our goals and always draw a blueprint until the end, so we have always moved forward smoothly and firmly, which is the difference between our two countries.”

NASA must constantly adjust to new leadership, while China benefits from long-term consistency.

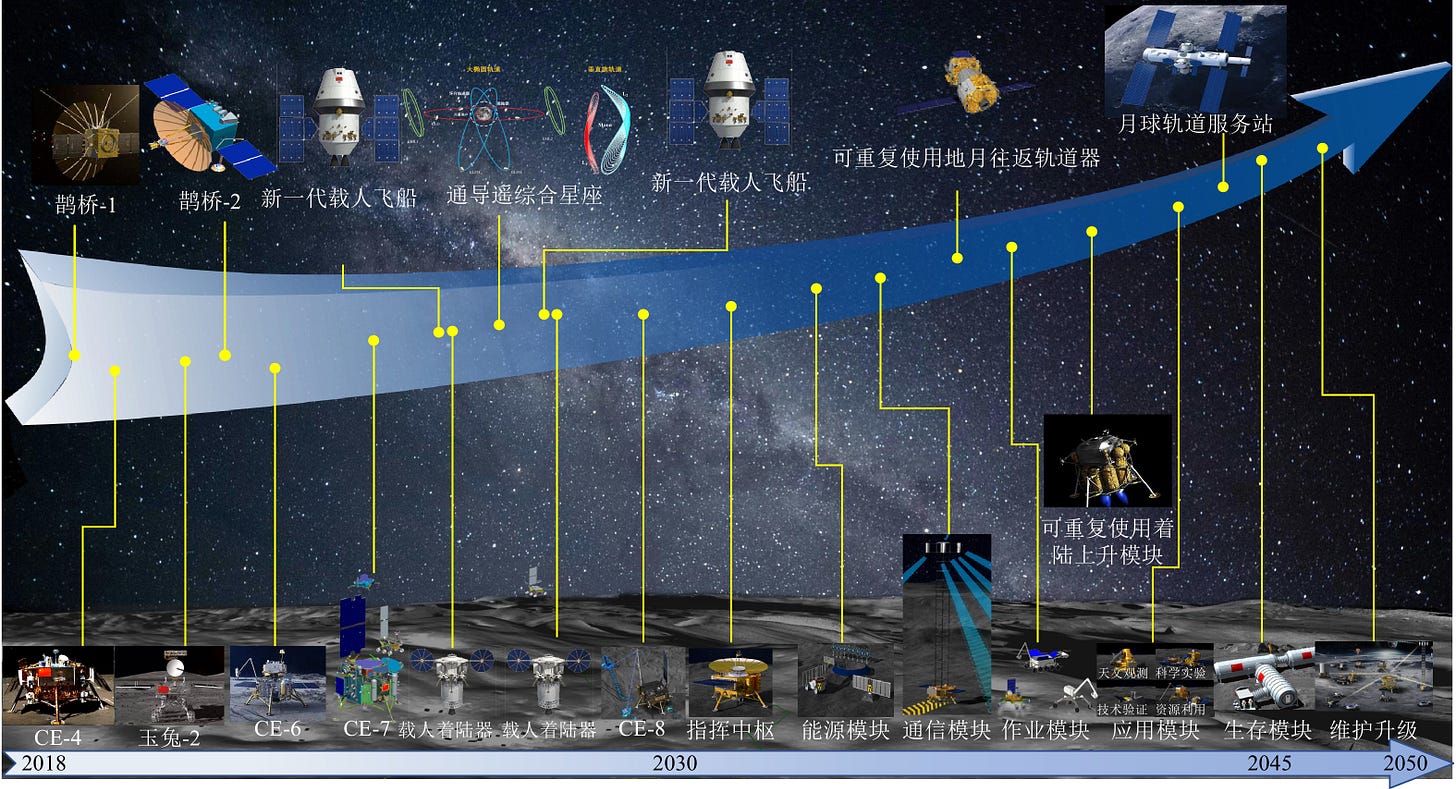

This is evident as both nations supposedly have plans for a long-term presence around the Moon, but only China has missions planned in support of that presence currently. At the center of China’s long-term Moon plans is the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), which will be a lunar surface base home to both robotic and crewed missions, with numerous international partners onboard. ILRS efforts will begin with Chang’e 7 and Chang’e 8 in 2026 and 2028, respectively, with further missions after 2030. Later missions will include the establishment of the Queqiao lunar relay network, human-rated long-term surface habitats, and a potential crewed lunar orbit space station.

Meanwhile, the U.S. has debated on how it should maintain a presence around the Moon, with an occasionally crewed lunar space station, small commercial robotic landers, or just canceling the Artemis program after returning astronauts to the Moon.

With the indecisiveness of the American program, it would make sense for the U.S. to reconcile with China for a more stable exploration program and head to the Moon together, right?

China has publicly expressed a willingness to cooperate with the United States in space, including on lunar exploration. Officials from the China National Space Administration have repeatedly stated that space should be a domain for peaceful use and international collaboration. But American law prevents cooperation, with Wu Weiren adding:

“We welcome exchanges with China and the United States, right? We want to communicate, but he is not willing to communicate with us now,” — “Our door is open, but his door is closed.”

As both nations move toward returning humans to the Moon, their approaches reveal deeper differences in governance, planning, and national priorities. The U.S. sees the Moon as a proving ground in a geopolitical contest, while China views it as an extension of long-term science-driven development. Whether this divergence leads to separate spheres of lunar influence or eventual cooperation remains to be seen.

For now, with current plans, America will likely put a crew on the Moon ahead of China, but China will go to the Moon more routinely, allowing for a greater bounty of science and national prestige.

This post is a rewritten, updated, and improved version of “Racing Nobody: America’s misunderstanding of China's lunar ambitions?”, published in August 2024.

This is explained for an entry-level audience well in Arthur Kroeber’s book ‘China’s Economy’ (2020), specifically the second edition, in chapter three ‘China’s Political Economy’. ISBN: 978-0-19-094646-3

The economist David Daokui Li is one of these knowledgeable academics the party will call upon regarding specific issues. He explains this in his book ‘China’s World View’ (2024). ISBN: 978-0-393-29239-8