Intelsat-708: Accident, Aftermath, Controversy

China’s worst and most misunderstood space accident, in the west.

The debut flight of the Long March 3B, carrying Intelsat-708, is the worst space-related accident in China’s space-faring history. Nearly 30 years later, the events of February 15, 1996, and their aftermath are still debated in space circles today. So what went wrong and what happened afterwards?

Build-up to Launch

On April 24th 1992, Intelsat and China Great Wall Industry Corporation (中国航天科技集团有限公司) signed a contract for the launch of an Intelsat-7A satellite to a geosynchronous transfer orbit. This was the sixth time a U.S.-built satellite was contracted for launch on a Chinese rocket, after five launches of Hughes-built AsiaSat and Apstar spacecraft.

Ahead of the launch, Intelsat-708 would need to be manufactured and the Long March 3B would need to finish development.

Developed by Space Systems/Loral, today known as SSL and owned by Maxar, Intelsat-708 was part of Intelsat’s Intelsat-7A program, which was based on the SSL-1300 spacecraft bus. Intelsat paid Space Systems/Loral almost one billion United States Dollars for nine satellites, including three for the 7A program.

Once in space, the satellite would have weighed 4,180 kilograms and had twenty-six C-band and fourteen Ku-band antennas, powered by two large four-panel solar arrays. Had the satellite reached orbit, it would have gradually maneuvered into its geostationary orbit slot to provide communications services for fifteen years.

Beginning in 1986, the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (中国运载火箭技术研究院) developed the Long March 3B launch vehicle to serve national and international customers seeking launches to geostationary orbit and beyond. By 1989, development was fully signed off, and funding for the realisation of the vehicle was approved in 1993, along with completion of its initial design.

To shorten the time between approval and launch, the Long March 3B is based off of the Long March 2E and Long March 3A, along with experiences from the Long March 3. Component-wise the vehicle inherited its four boosters from the Long March 2E, while its third-stage was from the Long March 3A and majorly improved. Both vehicles had flight experience prior, with the Long March 2E having flown seven times and the Long March 3A flying twice by early 1996.

By the end of development, the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology had a rocket capable of sending 5,100 kilograms to a geostationary transfer orbit that stood 56.3 meters tall and massed approximately 458,000 kilograms. For propellants, the first two stages and four boosters of the Long March 3B burned Dinitrogen Tetroxide and Unsymmetrical Dimethylhydrazine, with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen burned in the third-stage.

Ahead of the completion of the development and manufacturing of Intelsat-708 and the Long March 3B, the U.S. State Department granted Space Systems/Loral a license around September 18th 1992 to send their Chinese counterparts technical data in support of launch discussions. Additionally around July 14th 1993, an export license was issued allowing Intelsat-708 and any necessary equipment to travel to China.

In 1994, representatives from Intelsat and Space Systems/Loral traveled to China to inspect the Xichang Satellite Launch Center. Comparing the site to U.S. and European ones, a representative of Intelsat described the launch center as “primitive but workable”, it is unclear whether this was while in China or after returning.

Finally, around January 11th 1996 the Intelsat-708 spacecraft was shipped from the U.S. to China for integration atop of the Long March 3B.

In the days leading up to launch, the Long March 3B vehicle was stacked at Launch Complex 2. Beginning with the first-stage, followed by the four boosters, then the second-stage, and then the third-stage, before finally placing the payload atop the vehicle inside a fairing. Integration of the satellite into the fairing was happening inside a debris and climate-controlled facility at Xichang while stacking was ongoing on the launch pad.

For staff and U.S. visitors at the Xichang Satellite Launch Center, supplies of food, water, oxygen, and rescue equipment were restocked to ensure people can survive at least 24 hours in the event of an emergency. Additionally, an emergency chain of command was prepared, including a first aid unit and a firefighting team, on-site with ambulances, helicopters, and various vehicles nearby.

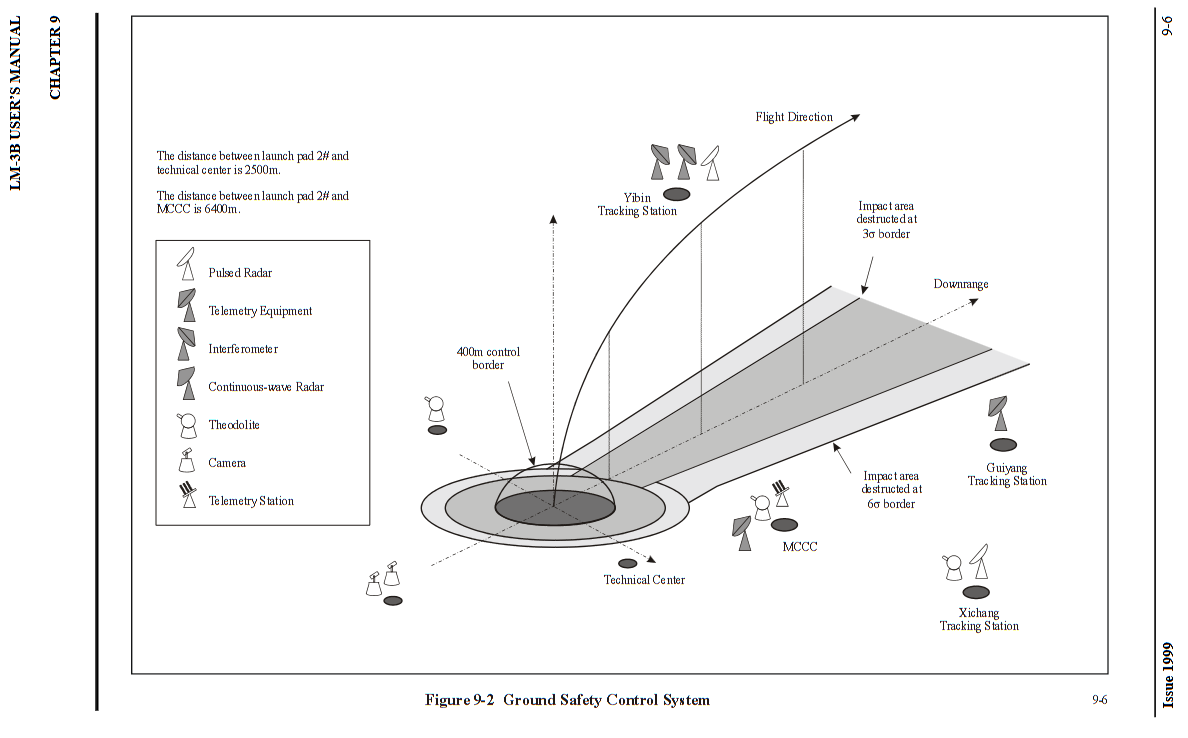

The following flight termination criteria were also programmed into the Long March 3B1:

If all the tracking and telemetry data disappear for 5 seconds, the launch vehicle will be destroyed immediately.

If the launch vehicle flies toward the reverse direction, the safety commander will select a suitable time to destroy the launch vehicle considering the impact area.

If the launch vehicle flies vertically to the sky other than pitches over to the predetermined trajectory, it will be destroyed at a suitable altitude.

If the launch vehicle shows obvious abnormal, such as roll over, fire on some parts, it will be destroyed at a suitable time.

If the engines of launch vehicle suddenly shut down, the launch vehicle will be destroyed immediately.

If the launch vehicle exceeds the predefined destruction limits (including attitude being unstable seriously), it will be destroyed at a suitable altitude considering the impact area.

If the launch vehicle is horizontally closer than 400m away from the launch pad, the launch vehicle will not be destroyed to protect the launch site.

If the launch vehicle leaves the normal trajectory and flies to the Technical Center during 15~30 seconds and Z≥400m, the launch vehicle will be destroyed immediately to protect the Technical Center, here Z is the distance between launch vehicle and the normal launch plane.

If launch vehicle is flying out of the safety limit for 30~60seconds, it will be destroyed immediately to protect MCCC.

Those outside of the Xichang Satellite Launch Center, like residents of nearby villages and tourists who travel to see launches, were informed of a launch in the coming days. As normal practice since 1984, on February 14th (the launch was scheduled for early on the 15th), local residents were requested to leave anywhere within 2,500 meters of the launch site, and those out to 6,000 meters away were asked to gather in large open pre-organized spaces. Anyone further downrange of the launch site was notified of the launch, along with being provided instructions on potential hazardous areas and materials.

With all preparations made for Intelsat-708 and the Long March 3B completed, and evacuations performed, the launch was set for around 03:00 am China Standard Time on February 15th 1996.

Launch & Failure

On February 15th in the leadup to liftoff, launch teams entered a nine-minute hold at T-02:51 followed by a forty-five-second hold at T-01:00. Once these holds were cleared, the launch continued. At 03:00 am China Standard Time, the Long March 3B carrying Intelsat-708 lifted off. The timeline of launch is as follows (T+minute:second, T represents the moment of ignition in China):

T+00:00: Engines on the Long March 3B’s first-stage and boosters ignite.

T+00:02: Long March 3B lifts off from Launch Complex 2.

T+00:04: Long March 3B begins pitch-over maneuver early.

T+00:06: Long March 3B heads of the top of the launch tower, while continuing to pitch over.

T+00:08: Long March 3B clears Launch Complex 2’s launch tower.

T+00:14: Long March 3B has pitched over 90 degrees, and is now beginning to pitch down toward the ground.

T+00:21: Long March 3B has pitched over another approximately 45 degrees.

T+00:23: Long March 3B vehicle begins to disintegrate while airborne due to aerodynamic stress.

T+00:25: Long March 3B vehicle collides with a hillside, ending the flight and sending out a shockwave.

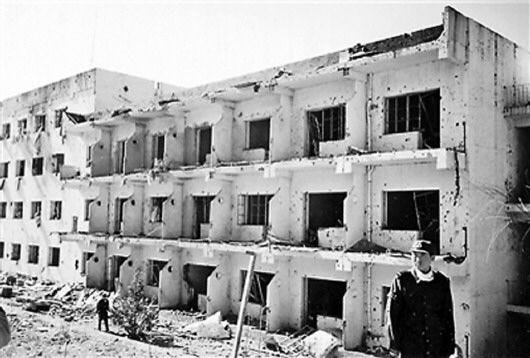

In its debut flight, the Long March 3B evidently did not reach its intended geostationary transfer orbit. During the approximately twenty-five-second flight, the vehicle flew some 1,720 meters from Xichang’s Launch Complex 2 to a hillside next to the launch center’s gate, where worker residences and work facilities are located.

After the debut mission ended abruptly, teams from China and the U.S. went to work on figuring out the root cause of the failure. By the end of February, teams had localized the failure to the vehicle’s inertial measurement platform, and then by mid-May concluded that a circuit fault was the most likely cause. Additionally, through June and July, further analysis indicated a poor gold-aluminum bond inside the measurement platform’s power module for a follow-up frame’s servo-loop caused the hardware to miscommunicate with the rest of the inertial platform. To simplify, a weak connection in the power unit caused communication errors in the navigation system, leading to the failure.

Cleanup & Casualties

Following the impact of the Long March 3B into the hillside some 1,720 meters away, the Xichang Satellite Launch Center’s disaster response processes were implemented. These processes, according to a Smithsonian article with a shaky narrative2, included gathering all personnel inside the center’s spacecraft fuelling facility as the most secure area, shutting down all air conditioning systems to prevent any new, possibly dangerous, air from entering the building, and handing out toxic gas detectors, gas masks, and protective equipment. The protective equipment was only given to the American workers.

Following no toxic gases being detected along the route to the Intelsat employee’s accommodation, a bus arrived to take the Americans to the city of Xichang. A few American’s however, snuck away prior to the bus arriving, which is what the Smithsonian article is based upon. The Americans not being allowed to leave the center was to prevent a possible diplomatic incident where a foreign national injured themself, thankfully those who snuck out were not injured.

While the Intelsat employees were waiting for transport, the local People’s Liberation Army garrison was called in, along with medical personnel and ambulances, to assist in response to the accident. The People’s Liberation Army’s primary role was to secure the perimeter of the now clean-up site following the accident and to assist American and Chinese engineers where necessary. Medical personnel sought to help injured workers at the launch center and those affected by the rocket’s shockwave.

In the weeks that followed, after part of both countries’ teams flew home, a thorough cleanup was conducted to collect debris from the Long March 3B and Intelsat-708. Parts for both vehicles were meticulously identified by the Chinese-American clean-up team. Intelsat-708 was sent back to the United States in its many pieces afterwards, apart from encryption devices that had been destroyed.

Two weeks following the accident, the Xinhua News Agency released a press release on the accident’s causes and casualties, stating:

“According to analysis and interpretation of telemetry data, it is considered that the accident was caused by changes of inertial baseline after lift-off. The particular cause is to be further analyzed and verified … At 3:01 on 15 February, our country’s newly developed Long March 3B carrier rocket lifted off. Anomaly in flight attitude appeared about two seconds later. The rocket pitched down and went right off the flight path. About 22 seconds later, the rocket crashed with nose down and exploded violently. Both the rocket and the satellite were lost. There were no large debris on the site … Up to today, 49 of 57 wounded have been cured and discharged from hospital and 8 are still in hospital. Arrangement has been made for the 6 dead. Checkout and testing shows that launch and testing capability of the Xichang Satellite Launch Centre was not affected … It is able to resume normal operation at beginning of March. More than 80 local houses nearby the launch centre were damaged. The launch centre and the local government provided temporary housing and relief fund to the victims … Except for short time pollution at the explosion site and in air, water source, plant and food were not polluted … China Great Wall has informed all customers and the international insurance industry progress of the investigation. On 28 February, Intelsat was invited to participate in the investigation.”

The official count of those killed during the Intelsat-708 remains at six, as of 2016. Western media has claimed that the accident wiped out the village of Mayelin, but based on population data, that is untrue. Between 2007 and 2010, the village grew from 1,200 people to 1,600 people and has been seen to continually grow since the accident. It is possible that the total number of dead may be higher, but it is likely still single digits.

Aftermath

Seeing an opportunity, the failure of the Long March 3B was included in the infamous Cox Report through its 1995 to 1998 information gathering effort. The Cox Report, officially titled "Report of the Select Committee on U.S. National Security and Military/Commercial Concerns with the People's Republic of China", was released by the U.S. House of Representatives in 1999 under the Chairmanship of Representative Christopher Cox (Republican), whom the report is named after. In the report, it was alleged that China had systematically stolen American nuclear weapons secrets over decades, including designs for warheads, and had benefited from technology transfers through commercial satellite launches and other cooperative programs. The Long March 3B failure became a point of interest for the report because American engineers had helped the Chinese side investigate the crash and improve future launches.

The committee behind the report argued that this technical assistance violated export control laws and potentially enhanced China's ballistic missile capabilities, since the same technology used for satellite launches could be applied to military missiles. As such, the report painted a picture of widespread Chinese espionage and technology acquisition efforts targeting American defense contractors, national laboratories, and aerospace companies.

However, the report was criticized as politically motivated and factually flawed. Many argued that it grossly exaggerated security threats while downplaying the routine nature of international space cooperation and legitimate technology-sharing agreements. Critics point out that the alleged "stolen" nuclear secrets were largely based on outdated designs already available in scientific literature, and that China's space program developments were primarily the result of indigenous research and development rather than espionage.

Following the report, in March 1999 the United States reclassified commercial satellites and their components as weapons under the country's International Traffic in Arms Regulations, commonly known as ITAR. As a result, satellites were moved from the jurisdiction of the Department of Commerce to the Department of State, which imposed much stricter export rules. The policy was eventually reversed in 2014 to ease restrictions and boost competitiveness. However, U.S.‑made satellites and their components still cannot be exported to China under American law.

Coincidentally, when satellites were disallowed for export, the U.S. was flying Atlas IIAS, Titan IV, and Delta III, to geostationary orbit at the time of the ban, while developing Atlas V and Delta IV. All were less competitive than the Long March 3B.

Meanwhile, things were not over for the developers of Intelsat-708. Between April 1996 and January 2002, Space Systems/Loral and the U.S. government were involved in a lengthy export control case due to the alleged transfer of critical defense technologies to China. The case would conclude with the company agreeing to, while not needing to admit fault of deliberately transferring technology, dole out 20 million United States Dollars, fourteen million for a fine paid to the Department of State and six million for expanding their export control compliance measures.

Since its failed debut flight, the Long March 3B went on to perform its second flight eighteen months and three days later, which was a success. Since then, the vehicle has flown over one hundred times, with two partial failures in 2009 and 2017, along with a total failure in 2020, resulting in the vehicle falling into the central Pacific.

Discussions Today

Up to now, we have been discussing the events and aftermath of the Intelsat-708 launch accident as they occurred. In a sensible world, discussion around the events with be discussed using factual evidence. Instead in the U.S., discussion in the aftermath has been captured by anti-China ‘hawks’ to enable the barring of China from American-linked international space projects and the global launch market.

Particularly in America and the English-language media, there is no trust in any Chinese account of the accident. This is most evident in the Smithsonian’s 2013 piece touched on earlier, itself used as a key part of any reporting since around the event. The lack of trust of any non-Western accounts in English-language media has unfortunately led to several conspiracy theories around Intelsat-708, including that the accident was deliberate3 or that thousands of people were moved in to replace Mayelin’s citizens4. Wikipedia is playing a part in this too, hosting falsehoods identifiable as false through satellite imagery.

By contrast, in China, the reasons why the launch failed are understood, along with accepting that people died in the aftermath while damaging, but not wiping out, the village of Mayelin. Every few years, Chinese outlets discuss and recall the events5. Even Long Lehao (龙乐豪), Chief Designer of the Long March 3B, has gone on record repeatedly recalling the events of Intelsat-708. Others who experienced the event are on record too in a China Central Television documentary called “Shaking the Heavens (撼天记)”, embedded below.

Comments & Sources

Work on this article began way back in early February, with intermittent work as sources were found, discussions were had, and sections were rewritten, including entirely in some instances. As for why work began in the first place, the Intelsat-708 accident has consistently been used as a ‘gotcha’ in conversations related to China's space progress by those outside the country. I hope that by thoroughly going through the lead-up and aftermath of the accident, a more easily understandable recount of the event exists moving forward.

Some sources are linked and cited multiple times. I have done this as some readers may only be interested in a specific section. As I expect some readers to focus on a specific section, no abbreviations have been used.

The videos uploaded by me and embedded in the article, which are hosted on YouTube, have not been altered in any major way. The only modification made was to split the footage into two separate videos, one for the launch footage and one for the aftermath of the failure. I have embedded some else’s copy of China Central Television’s documentary and apologise in advance if it is taken offline.

From the 1999 users guide, earlier versions exist but are not archived online.

How retrieving useful, reverse engineerable hardware from an impact of substantial force happens is highly questionable. If China wanted technology from Intelsat-708, it was in a launch processing facility for four weeks ahead of the accident, yet much of it was recovered afterward.

If Mayelin’s population was wiped out, it would have been easier to erase the village rather than rebuild it with new materials.

Please see the following, as I cannot place four links in a single hyperlink:

Good article on this topic. However i have to clarify something; the village of Mayelin actually wasn't 1 km away; thats the town of Mayelin you're talking about. Mayelin village was located right at the main gate of the launch center and stretched to Mayelin town. Chen Lan made that mistake in his Space Review article on the launch and now people believe it. Other than that the article is pretty good at explaining that failed launch.

Great work! And I think it's very important.

有耳能听,有心能会