Replacement Shenzhou-22 Spacecraft to Launch in a Week

To maintain Tiangong's scientific value, a new spacecraft will be sent up uncrewed.

On November 14th, the Shenzhou-20 crew of Commander Chen Dong (陈冬), Operator Chen Zhongrui (陈中瑞), and Science Operator Wang Jie (王杰) returned to Earth via the Shenzhou-21 spacecraft after theirs was found to have a damaged window following a space debris strike. That choice by the China Manned Space Agency left the Shenzhou-20 spacecraft docked to the Tianhe module’s Earth-facing port at the Tiangong Space Station.

At present, the Shenzhou-21 trio, who arrived on November 1st, of Commander Zhang Lu (张陆), Flight Engineer Wu Fei (武飞), and Payload Expert Zhang Hongzhang (张洪章), has the Shenzhou-20 spacecraft as their emergency Earth return spacecraft, but it will not be suitable for a regular return (as will be discussed later). To solve that issue, on November 15th, it was announced that the Shenzhou-22 spacecraft will be delivered to the taikonauts on board Tiangong, with standard mission preparations underway since around November 11th.

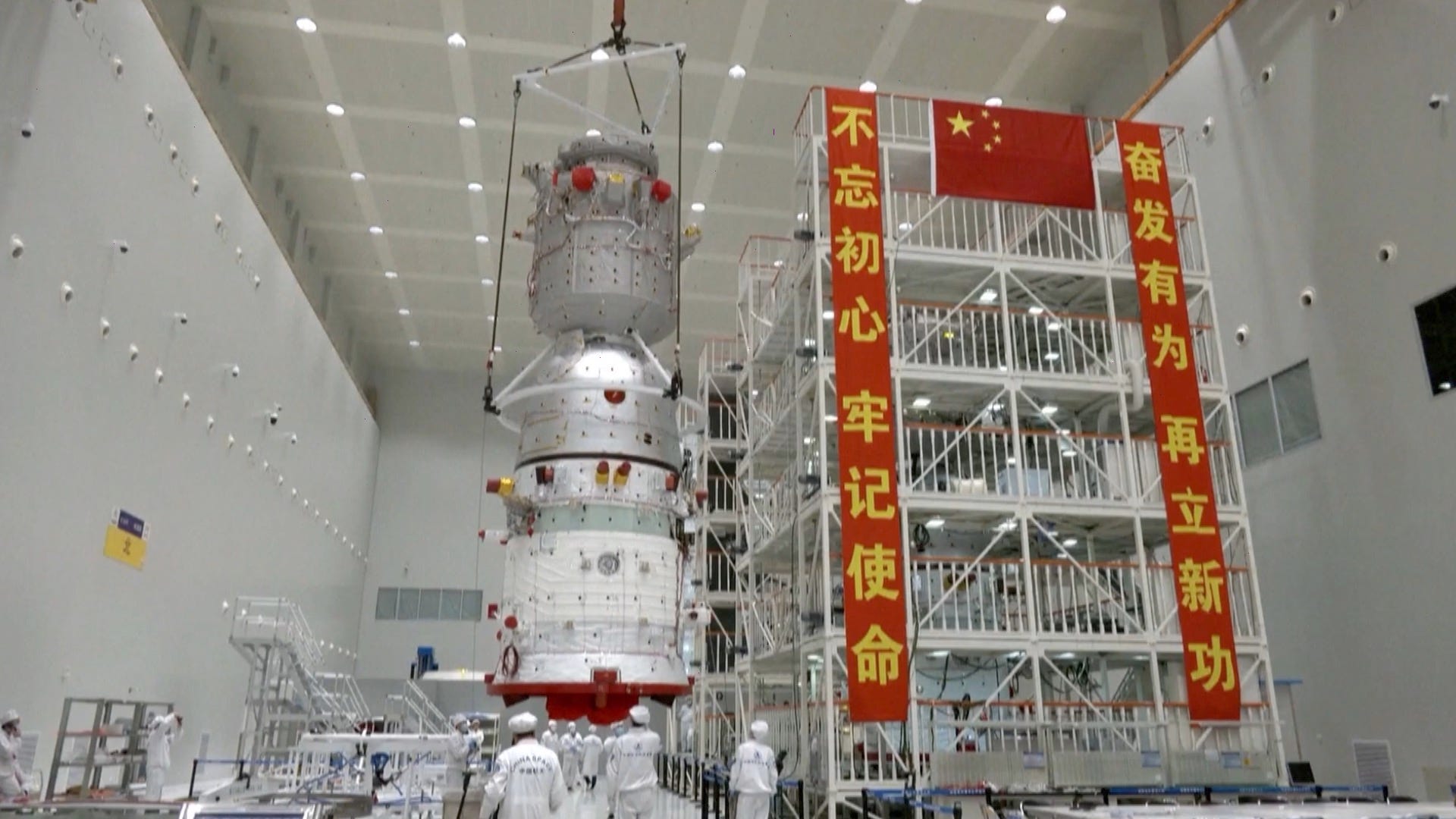

For that delivery, the Shenzhou-22 spacecraft will fly uncrewed and autonomously to Tianhe’s forward-facing port, carrying cargo in the extra space freed up by a lack of taikonauts1. Zhou Yaqiang (周亚强) of the China Manned Space Agency said the following regarding the launch:

“The mission for launching the Shenzhou-22 spacecraft has been initiated, with all preparations for all systems in full swing, including testing the spacecraft and rocket components and preparing the cargo. . . . The spacecraft’s cargo-carrying capacity is a highly valuable resource for the manned space program, so we will make full use of every opportunity. The Shenzhou-22 spacecraft will mainly deliver food supplies for the astronauts and some equipment for the space station.“

Those food supplies will mainly be to replace that consumed by the Shenzhou-20 and Shenzhou-21 crews during their thirteen-day stay onboard together, basically refilling the space station’s stocks to their standard planned levels2.

As of November 18th, notices suggest that a Long March 2F/G will carry the Shenzhou-22 spacecraft on a launch toward Tiangong on November 25th at around 12:11 pm China Standard Time (04:11 am Universal Coordinated Time). It will also be the first uncrewed Shenzhou launch since Shenzhou-8 in November 2011 to the Tiangong-1 station3.

Once the new spacecraft is docked to the space station, the Shenzhou-20 spacecraft will return to Earth uncrewed, with easily reproducible experiments, waste items (like worn clothing), and other cargo. Nothing critical, like retired Feitian (飞天航天服) spacesuits, will be sent down with it due to risks from the damaged window.

Following the launch of Shenzhou-22 next week, the production and delivery of the Shenzhou-23 and Shenzhou-24 spacecraft and their launch vehicles are expected to be expedited4 to maintain a busy and important schedule in 2026. That will see those spacecraft carrying a taikonaut for the station’s first yearlong stay, as well as a brief visit from a Pakistani astronaut.

Never stranded

With the Shenzhou-20 spacecraft being the only crew-rated vehicle docked to Tiangong and while the Shenzhou-20 taikonauts were onboard, several outlets, including Ars Technica, the South China Morning Post, Space.com, Gizmodo, and Wired, have stated that those in space are stranded. That is false.

As I have explained before, the Shenzhou spacecraft has two windows, each with four glass layers. Only the outermost layer is designed to withstand reentry heating, meaning that a failure of this layer could compromise the remaining three layers, leading to depressurization. However, this does not stop the Shenzhou-20 spacecraft from serving as an emergency return vehicle if needed. All three taikonauts wear pressurized suits during their descent to Earth, ensuring their safety even in the event of depressurization of the spacecraft. While a depressurization would degrade or ruin most experiments returning with the crew, they would remain safe.

It did not help that the China Manned Space Agency’s comment on the Shenzhou-20 spacecraft required knowledge of Tiangong’s emergency contingencies, with part of it stating:

“This condition does not meet the clearance criteria for a safe manned return. The spacecraft will remain in orbit to conduct relevant experiments.”

So why the choice to use the Shenzhou-21 spacecraft for the November 14th return? Mainly, Tiangong is an orbiting microgravity laboratory, having its value (the resources China’s government allocated to build and maintain it) linked to how much science the station can perform. At the moment, scientific data that a downlink of information will not be sufficient for has to come back via the Shenzhou spacecraft (like mice). Recognising the limited returns Shenzhou missions perform5, the Haolong (昊龙) cargo spaceplane is under development for use within a few years to provide greater experiment return opportunities. A secondary use of Tiangong, still tied to its main one, is to understand how the human body adapts to, works, and lives in the microgravity environment. Taikonauts also assist in the running and maintenance of experiments.

Through the launch of the Shenzhou-22 spacecraft next week, Tiangong will resume its normal operations with its nominal return option, for science and taikonauts, having given mission planners real-world experience in once purely theoretical emergency practices6.

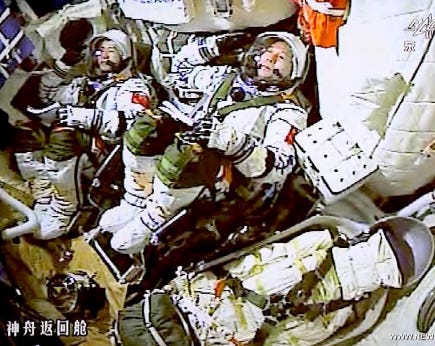

Without the customized seat-lining cushions, seats in the Shenzhou spacecraft can hold cargo using the same straps used for taikonauts. See an example from Shenzhou-11 in 2016:

Those necessary for a standard six-month mission, plus extra, onboard the space station.

Technically, the current Tiangong Space Station is Tiangong-3. China’s first two space stations, Tiangong-1 and Tiangong-2, had the same name. The first two stations were single modules and later served as the basis for the Tianzhou cargo resupply spacecraft.

Also allowing for the continued backup plans, which has a Shenzhou spacecraft and Long March 2F/G rocket ready to launch within 8.5 days if needed in the case of an emergency.

One each for two per year.

The quick inspection and determination of a spacecraft’s suitability to carry out its mission unimpeded, as well as the readiness of a replacement spacecraft.