Second Xihe Sun-Monitoring Mission Set to Launch in 2028 or 2029

Later this decade, a new satellite in deep space will improve our understanding of the Sun and monitor space weather events.

At the start of the month, China’s various media outlets reported that the Xihe-2 (羲和二号) mission, formally known as Lagrange-V solar observatory (LAVSO), to observe the Sun will launch later this decade, signaling that it has been approved by the nation’s government.

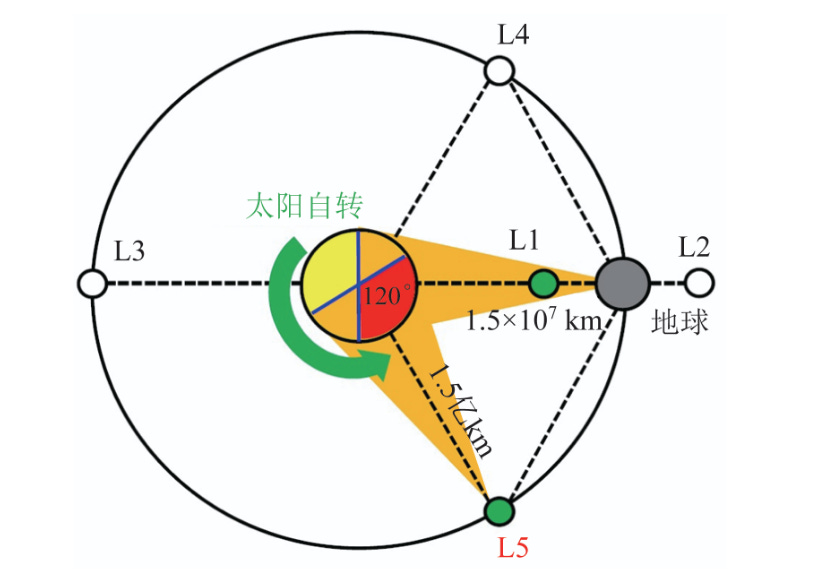

At present, the Xihe-2 mission is set to begin between November 2028 and July 2029, with a liftoff atop of a Long March 3C from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center. That launch will throw the 1,700-kilogram spacecraft out into deep space, where it will fly for approximately 480 days to reach the L5 Sun-Earth Lagrange point1. Once there, it will operate for at least five years, with an aim of beaming back 230 gigabits of data each day.

Reports about it highlighted that the mission will be the first spacecraft in the L5 point, following Earth in solar orbit at a distance of about 150 million kilometers. By being based at that point, those involved with the mission posit that the Xihe-2 spacecraft will be able to detect which regions of the Sun are active around four to five days earlier than existing spacecraft and instruments on Earth. Li Chuan (李川), Chief Designer of the original Xihe mission’s scientific and application system at Nanjing University’s School of Astronomy and Space Science (南京大学天文与空间科学学院), expanded on that, telling Xinhua:

“To date, humanity has launched over seventy solar probes2, with the vast majority positioned along the Sun-Earth orbit and a few orbiting the Sun. No probe has yet been stationed at the Sun-Earth L5 point. Therefore, Xihe-2 will offer humanity a completely new ‘bystander’s perspective’ for solar research.”

If there are any problems with this translation please reach out and correct me.

Nanjing University Professor Ding Mingde (丁明德), Chief Scientist of the first Xihe mission and participant for Xihe-2, told Global Times that the upcoming spacecraft will improve space weather predictions and early warnings for ejections from the Sun. Alongside that, the mission will look to understand the generation and evolution of solar magnetic fields, as well as their links to solar eruptions, why those eruptions spread, and their relationship to harmful space weather3.

In order to monitor the Sun and research it, Xihe-2 will have five instruments, detailed in a Nanjing University paper titled ‘Overview of the Lagrange-V Solar Observatory (日地L5太阳探测工程概述)’. Those instruments are4:

Vector Magnetograph: measures the three-dimensional magnetic field vector and plasma velocities in the solar photosphere using polarized light spectroscopy.

Extreme Ultraviolet Imager: observes the solar corona in two key wavelengths to capture the evolution of pre-eruption magnetic flux ropes and current sheet structures during flares.

Coronal and Heliospheric Imaging Package: a white-light coronagraph images coronal mass ejection initiation and early acceleration near the Sun, while the heliospheric imager tracks their propagation through interplanetary space.

High-Energy Radiation Spectrometer: detects hard X-rays and gamma rays to determine non-thermal electron and ion acceleration sites during flares.

In-Situ Detection Package: measures solar wind plasma parameters, energetic particles across multiple energy ranges, and interplanetary magnetic field vectors at the L5 point.

Other Xihe solar missions

When Xihe-2 does launch, it will be several years after its precursor mission, Xihe (羲和), formally called Chinese H-alpha Solar Explorer (CHASE), launched in October 2021. Since being placed into sun-synchronous orbit around Earth, the spacecraft has been regularly imaging the Sun with its H-alpha spectrometer to understand activity in the photosphere and chromosphere. As of December 2025, Xihe has reportedly transmitted 1.2 petabits of scientific data.

Scientists involved with the two missions don’t plan to halt exploration of the Sun with Xihe-2, with the proposed 2030s Xihe-3 (羲和三号) in an inclined orbit to observe the poles, while a hypothetical Xihe-4 (羲和四号) would make close approaches to regularly measure particles. Working together, the four Xihe missions5 would be routinely monitoring solar activity.

All of those approved and proposed missions are named after the same deity, the mythological Xihe. According to legend, she is one of the two wives of Emperor Di Jun (帝俊), an ancient supreme deity, and the mother of ten suns that lived in a mulberry tree in the form of three-legged crows. One of those suns would travel around the world each day, guided by Xihe on a chariot. All but one were shot down after all ten travelled on the same day, burning the world, leaving just the Sun.

Via NASA’s ‘What is a Lagrange Point?’:

“Lagrange points are positions in space where objects sent there tend to stay put. At Lagrange points, the gravitational pull of two large masses precisely equals the centripetal force required for a small object to move with them. These points in space can be used by spacecraft to reduce fuel consumption needed to remain in position.”

Including NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, the European Space Agency’s Proba-3, and India’s Aditya-L1.

For example, coronal mass ejections that can cause damage to power grids and computer systems while disrupting radio signals on Earth. See the Wikipedia page for the March 1989 geomagnetic storm for more.

Full details are available on page six of the paper in Table 2 under Section 3.

The first Xihe spacecraft may need replacing by then.