Chinese News Outlets Say Giant Constellation Filing Is Lawful, Not Final Deployment Plan

And is a 193,000 satellite constellation in Earth orbit realistic at that scale?

Recently, Chinese spacecraft operators submitted filings to the International Telecommunication Union with plans for nearly 200,000 new satellites to build out new constellations and expand existing ones. Most of those satellites would, surprisingly, come from just one institute.

Not long after reports of the filings began to be released, Xinhua published a short report detailing the main points of the giant constellations and stating that building those networks would require the activation, promotion, and coordination of the entire space ecosystem within China. It also took a moment to state that other 100,000 satellite constellations have been filed for before at international bodies, like Rwanda’s never-launched 327,230 satellite network in 2021.

China Daily and the Global Times chimed in with similar reports, in English, to say the filings from the handful of operators that amounted to about 200,000 satellites are part of long-term planning rather than short-term visions of profit. They also added that the satellites must, at least, be starting deployments two to seven years after the filings or risk losing their allocation or downsizing plans.

In addition, China Daily’s piece felt it relevant to share:

“Large low-Earth orbit constellations can provide essential global public goods — bridging the digital divide, improving disaster response, supporting climate monitoring and extending connectivity to remote and underserved regions. These goals align closely with China’s vision of building a community with a shared future in outer space, where development, security and sustainability advance together.”

“Securing lawful access to limited orbital and spectrum resources today is not about exclusion, but about ensuring that outer space remains safe, open and beneficial for all humanity tomorrow.”

In another report that came out a few hours later than the others, also from China Daily, Yang Feng (杨峰), Founder and General Manager of commercial satellite maker Spacety (天仪研究院), detailed:

“China’s satellite internet development is characterized by nationwide coordination, in which different parties are involved. This has elevated satellite internet from a stand-alone commercial venture to the Chinese government’s new infrastructure effort.”

“Leading in terms of filing applications does not mean surpassing in final execution. Turning these plans into operational constellations faces major challenges in terms of systems engineering, manufacturing and launch capacity.”

All three outlets noted that filing for the constellation’s giant satellite counts does not mean they will launch, following coordination and feedback from other spacecraft operators, the allocation of available relevant orbits, as well as optimized plans from the operator responsible for the filing.

A little awkwardly, days before the filings, one of China’s representatives at the United Nations lodged an informal complaint at a Security Council Arria-Formula meeting regarding SpaceX’s Starlink's alleged gobbling up of spectrum frequency and orbital resources, interference in other countries, and risks to other spacecraft and space stations.

Are gigantic constellations realistic?

Regarding the execution challenges that Yang Feng spoke of, the Institute of Radio Spectrum Utilization and Technological Innovation (无线电频谱开发利用和技术创新研究院), mostly responsible for the giant filings with its two CTC networks boasting 96,714 planned satellites each, for 193,428 in total, will have major challenges in producing, launching, and operating that many satellites. Notably, not even two hundred mega-constellation satellites made it to orbit from China last year.

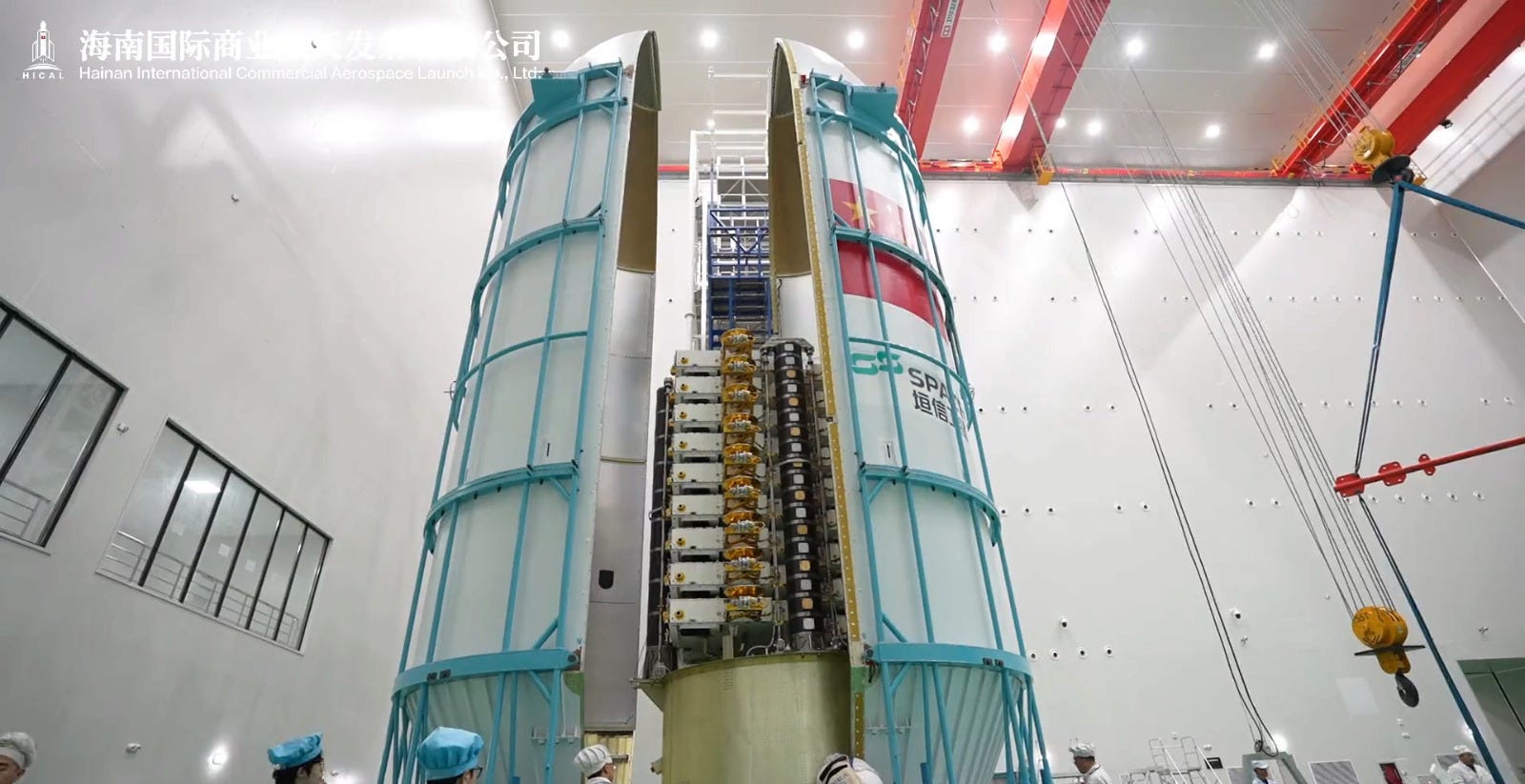

Making hundreds of thousands of satellites will be the first issue. At the moment, commercial satellite makers can reportedly make 300 spacecraft per year, with plans to expand up to 600, while state-owned enterprises can produce several hundred. This will be bolstered in the near future by a 1,000-satellite-producing ‘super factory’ near Wenchang’s two launch sites. Unrealistically assuming the CTC networks could buy all of that capacity, it would take them at least a century to reach their desired satellite count, assuming no investment in expanding that capacity.

Launching all of those satellites will be a major hurdle too. If the two CTC networks’ satellites are of a similar design to China’s serious mega-constellation efforts, anything from a handful to just over a dozen will be launched at a time. Those mega-constellations, despite being a commonly flown payload, have to share launch availability with other spacecraft as well. While China’s national launch cadence is ramping up, through producing more launch vehicles and reusing them, it would take a dozen decades at minimum to fill out the CTC networks.

After launch, operating and coordinating up to 193,428 satellites would be a major logistical headache. Through SpaceX’s 10,000-launched Starlink spacecraft alone, at least 144,400 collision mitigation manoeuvres take place every half year for a proven constellation that’s currently nineteen times smaller than the planned CTC networks. Risks of collisions can be lowered by heading to higher orbits to further spread out satellites, although coming with their own problems and assuming that no technical issues are experienced while in-orbit like the Shanghai-backed Qianfan (千帆) mega-constellation had.

Unless the Institute of Radio Spectrum Utilization and Technological Innovation has many billions, possibly trillions, of Yuan to expand satellite production and procure many, many launches, the CTC networks are very unlikely to launch at their currently planned scale. As was noted when the filings were noticed, those within China writing on them have suggested that, before downsizing, the giant filing is instead meant to trigger a global conversation on the International Telecommunication Union’s model of frequency allocation, following, from China’s view, the dominance of Starlink in low Earth orbit.